Reading Jim Thompson (1906-1977) is like stepping into a fevered dream just convincing enough to pass for reality. His “dime-store Dostoyevsky” novels don’t simply entertain—they drag you into the fragmented psychology of characters who aren’t merely criminal or immoral, but broken in ways they almost understand. That almost is key. Thompson doesn’t build his worlds on grand philosophical systems or dramatic arcs of redemption. He constructs them from the inside out, letting madness, delusion, and desperation seep through the cracks of small towns, cheap motels, and busted American dreams. These aren’t nihilists. There’s something unhealthy in them, yes… but they know what health looks like, even if it always stays just out of reach.

What makes them so compelling?

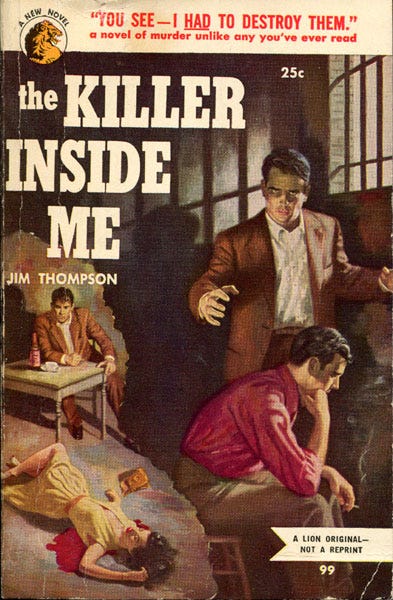

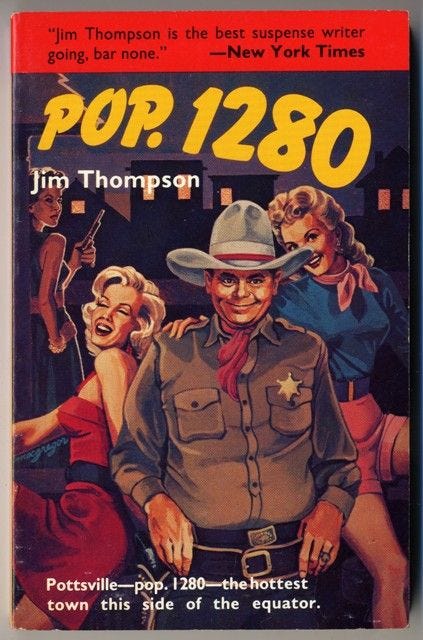

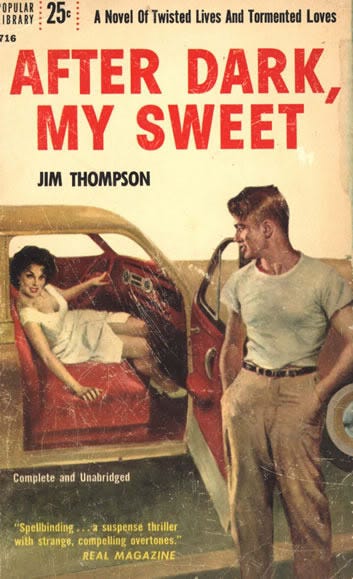

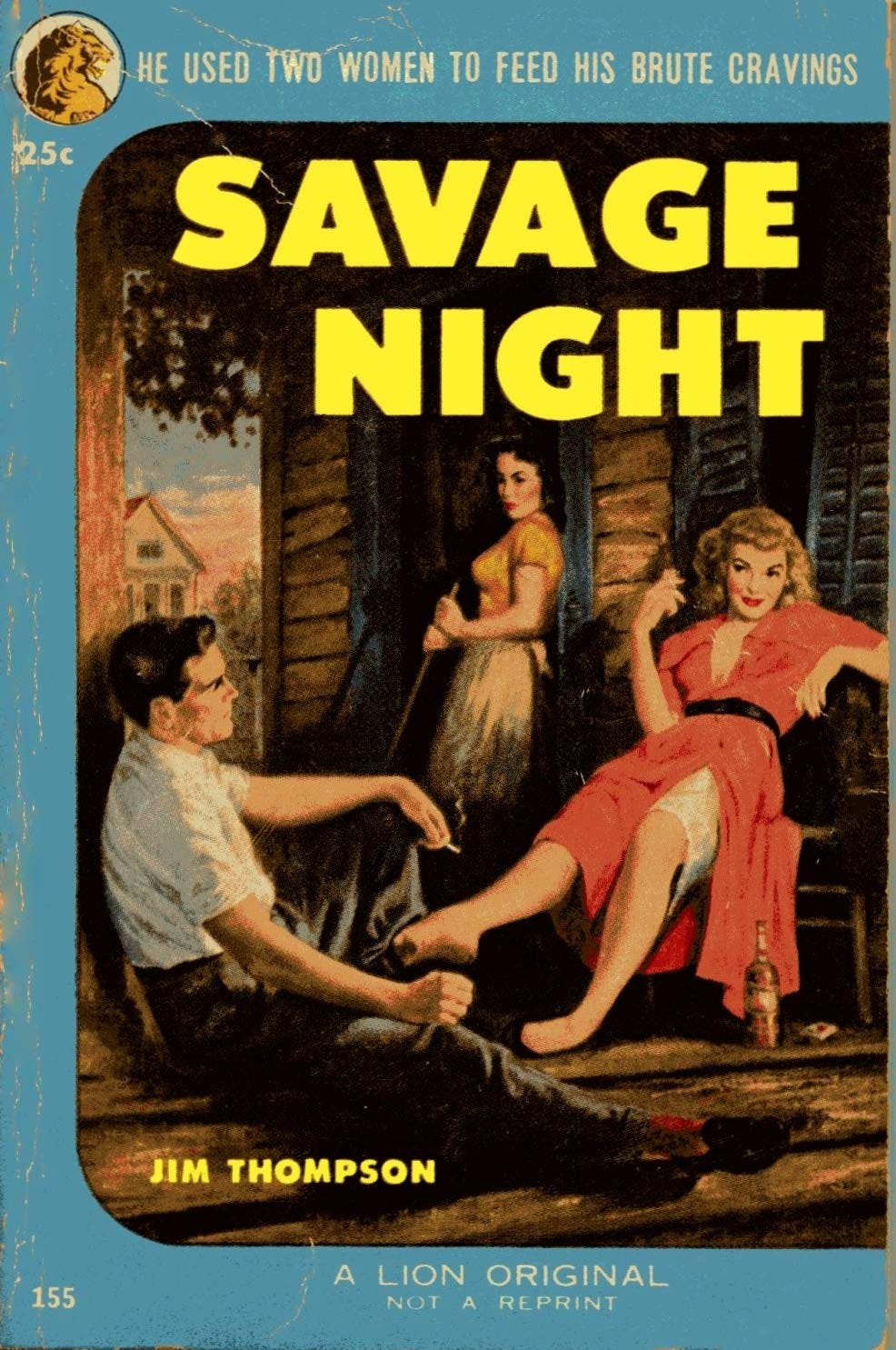

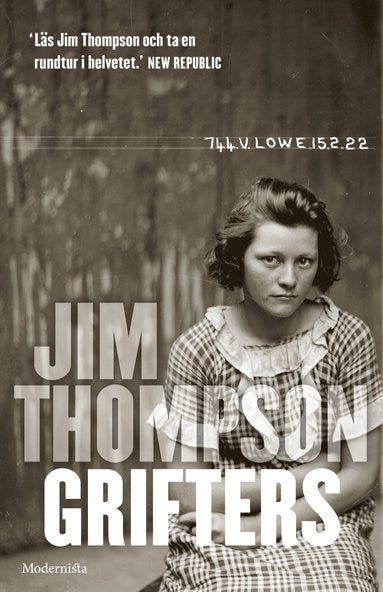

Thompson’s novels unfold in settings that mirror their characters’ unraveling: small-town Texas in The Killer Inside Me hides sadism beneath civic calm; Pop. 1280’s rural Southern town masks rot with folksy charm; Savage Night plays out in a cold, unnamed Northeastern town that feels like a fever dream; After Dark, My Sweet drifts through sun-bleached California desert towns where heat blurs reality; and The Grifters moves through Los Angeles, a city of surfaces and scams. In each case, the setting isn’t just a familiar backdrop for American readers: it’s a moral landscape, echoing the characters’ delusion, decay, or desperation.

Thompson’s characters aren’t navigating moral dilemmas… they’re already past that. They’re improvising survival, driven by impulse, fear, and a slippery kind of charm. In The Killer Inside Me (1952), Lou Ford embodies this perfectly. He’s a man who masks sadism with homespun wisdom, whose violence doesn’t come from ignorance but from a warped self-awareness. Thompson doesn’t ask the reader to forgive Lou—he dares you to understand him, to sit inside the claustrophobic mess of his mind and feel how persuasive that mess can be.

That’s one of Thompson’s key traits: the unreliable narrator. His protagonists don’t lie because they’re clever… they lie because they need to believe what they’re saying. The reader is often the last to catch on, lulled by the plainspoken prose until the gaps start showing. By then, you’re so far inside the character’s head that your sense of reality begins to distort. It’s not just storytelling—it’s entrapment. A sickness lurks.

Madness in Thompson isn’t theatrical. It’s structural. His narrators operate in split registers, where their actions and explanations diverge subtly, then violently. This psychological fracturing—paranoia, hallucination, guilt as static on the line—becomes the atmosphere. The world doesn’t go mad around the characters; it reveals that it always was.

And Thompson’s world is built on poverty and powerlessness. Unlike the metropolitan noir of Chandler or Hammett, his landscapes are dusty towns, diner booths, oil rigs, and crumbling porches. His characters aren’t glamorous criminals. They’re workers, cops, drifters. These Americans, this America, still exists. Their desperation isn’t a genre flourish—it’s economic, social, deeply personal. They don’t fall from grace; they’re born below it. And the horror comes from how familiar their options feel.

Then there’s the prose—so deceptively simple it often takes a second read to see the trapdoor beneath it. Thompson starts with clipped, conversational rhythms, then lets them slip. A phrase will tilt sideways, a line will echo strangely, and suddenly you’re reading a hallucination disguised as realism. Savage Night (1953) is the most surreal—it reads like noir melting in the sun. Its plot collapses on itself, its narrator dissolves, and what’s left is the uncanny residue of a story that should never have made sense—but somehow does.

Pop. 1280 (1964) leans into humor, but it’s the kind that curdles. Nick Corey’s dumb “golly-gee” persona hides sophisticated sociopathic cunning. The charm doesn’t make him less dangerous—it’s what makes his evil effective. He uses it like a weapon, making you laugh while he arranges your demise. Thompson writes with a grin you can’t quite trust.

Still, the violence in Thompson’s novels isn’t only male. His women don’t serve as decoration or saviors—they’re dangerous, wounded, manipulative, and sharp. Fay in After Dark, My Sweet may use Kid Collins, but she also shows flickers of tenderness and shared damage. Joyce Lakeland in The Killer Inside Me sees Lou Ford’s darkness but can’t escape it. Rose in Savage Night becomes a grotesque figure of revenge and desire, one leg shorter than the other, her power almost mythical. These women aren’t stereotypes. They’re survivors of brutal systems—sometimes monsters, sometimes victims… usually both.

And then there’s Carol Roberg in The Grifters (1963), who stands apart. A Jewish nurse and Holocaust survivor, she’s not a grifter or a killer—she’s competent, kind, and emotionally grounded. Her background isn’t emphasized heavily, but it lends her a quiet moral gravity. In a world built on con games and exploitation, she suggests a kind of healing might be possible—not through purity, but through resilience. She isn’t innocent, but she’s intact.

What makes Carol so powerful is her refusal to be drawn into Roy Dillon’s spiral—the struggle between his girlfriend and his mother, the pull of shame and deceit. When Roy mocks her trauma and turns away from the possibility of intimacy, she simply exits. No dramatics, no revenge. Just absence. That silence becomes one of the novel’s most devastating judgments.

Revisiting the book with her in mind, you begin to see how she subtly reframes the entire moral structure. She’s the road not taken—and the one both Roy and the novel quietly mourn. Her departure closes the only door that might have led somewhere better.

There’s no real justice in Thompson’s world, but there is gravity. His characters often get what they chase, even if they didn’t know what it was. The endings rarely offer catharsis. There’s no moment of transcendence, no noble last stand. If salvation exists, it’s in the form of silence—or in a door that shuts just before someone reaches it. And yet, the bleakness never feels gratuitous. It feels earned. There’s a pattern to the collapse. A kind of dreadful harmony.

That’s why Thompson’s novels compel us—not because they depict evil, but because they erode the boundary between sanity and delusion, between justice and survival. His characters aren’t monsters. They’re people who cracked under pressure…sometimes before the story even starts. The pleasure of reading him is masochistic, in the best way: we see the worst of ourselves magnified, lit by the flickering neon of a motel sign, and realize that the real horror isn’t what his characters do. It’s how close we come to understanding why they did it.

What makes Jim Thompson’s novels so compelling is their intimate portrayal of unraveling minds within a corrupt world that feels disturbingly familiar. He draws readers in through psychological immersion—you don’t just witness a breakdown; you inhabit it, seduced by a voice that doesn’t know it’s collapsing. His moral worlds are ambiguous, shaped by pressure rather than principle, and his prose lulls with plainness before tilting into unease. Thompson offers no redemption, but he never writes without meaning. His novels feel like confessions we weren’t meant to hear—but can’t stop listening to once we have.

In Thompson’s fiction, survival isn’t triumph. It’s just what happens when you run out of lies. His stories don’t end with redemption. They end with recognition. In the end, no one’s saved, but everyone’s exposed.

My books. More coming.