Karel Čapek (1890-1938), born in a small Bohemian village, was part of that sprawling multicultural giant, the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As this empire decayed, so many of its writers, artists and intellectuals produced timeless world-class work. In Decline of the West (1918), Spengler describes an empire in decay as a wildly flowering plant. It was not just the empire that decayed, but foundational beliefs of Western ways of life. So many things were changing. This disquiet seeped into Čapek's early works – plays and stories that wrestled with the complexities of alienation and the struggle to forge an identity in a world undergoing rapid metamorphosis. As Čapek himself observed, “We are suffocating in a world that is too full of things, and yet strangely empty of meaning.”

“Čapek” to English-trained ears sounds like CHAP-ek. His fiction and drama often explored beyond the real or natural. It ranged from science fiction, to speculative fiction, to the fantastic, to allegory, to stories hard to categorize. Sometimes he charged his stories with social criticism, targeted in a specific and contemporary manner, or at more general human error.

Aside from fiction, he wrote essays, travelogs, and journalism that crackled with observations of the social and political landscapes. He wrote a whimsical tale for children, Dog and Cat. His bibliography is long, and I have only read (or seen) two of his most famous works. Here are my thoughts.

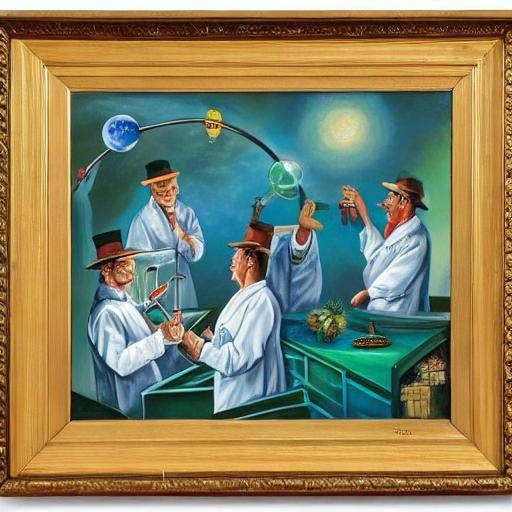

THE COMEDY OF SCIENCE

The Czech word robota means: forced labor, drudgery, servitude. In Karel Čapek's play R.U.R., the robots are a factory-produced workforce designed to relieve humans of drudgery. However, the play considers our dependence on labor in more than one way, and the potential dangers of creating a subservient class, even if that class is manufactured. These themes fill a circle in a Venn Diagram overlapping with the proletarian troglodytes of Well’s The Time Machine, the biological mashups of Well’s Island of Doctor Moreau, the genetic castes of Huxley’s Brave New World, and the medical resource clones of Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go.

Čapek's play R.U.R. (1920) centers around Rossum's Universal Robots, a company that creates humanoid robots out of “synthetic protoplasm” for manual labor. These robots are not metal creatures. They are biological. Rossum designed them to be the perfect workforce, but tensions escalate as characters grapple with the robots' rights and humanity's dependence on them. Helena, a character who initially welcomed the robots, voices growing unease: "But what are we to do then? What's the use of us?" (Act I). The love farce themes of the first Act fades as humanity, threatened, then sterile and hunted, itself fades away.

The proletarian robot revolution, and the fall of humanity, follows the reductio ad absurdum of purist, most efficient, ultimately inhuman capitalist logic that seeks to minimize labor costs to zero. This is a good thing, as we know in our time, except what about the replaced humans? Aren’t they going to be angry, and then what? Will they go on to another job… or will they take welfare, smoke meth and lie on the sidewalk, or join radicals and smash windows? We already know we need to help capitalism from destroying itself. Things keep changing and changing the balance. In R.U.R, the early model lumpen robots sometimes get “robot cramp”, break down and start smashing things, just like in Portland over the last few years. About halfway through the play, a robot complains, “I don’t want any master.”

Here’s a wonderful detail: to help the robots evolve, engineers gives them the ability to feel pain. Near the end, doomed humans argue if this helped the robots achieve a soul.

R.U.R. includes the immortal line, “Robots, attack!” But even the robots face unexpected consequences. With almost all humans dead, a new problem appears: the robots have a short lifespan, and can’t reproduce. If they destroy the humans, they destroy their future. This leads to a pause in the destruction, a compromise, and a hybrid resolution.

In an interview for a London paper, Čapek commented on R.U.R:

I wished to write a comedy, partly of science, partly of truth. The odd inventor, Mr. Rossum, is a typical representative of the scientific materialism of the last century. His desire to create an artificial man -- in the chemical and biological, not the mechanical sense -- is inspired by a foolish and obstinate wish to prove God unnecessary and absurd. Young Rossum is the young scientist, untroubled by metaphysical ideas; scientific experiment to him is the road to industrial production. He is not concerned to prove but to manufacture. . . . Those who think to master the industry are themselves mastered by it; Robots must be produced although they are a war industry, or rather because they are a war industry. The product of the human brain has escaped the control of human hands. This is the comedy of science.

Why do we associate the word robots with metal machines that imitate creatures? Maybe the idea of metal human-like machine slaves had already taken grip in world culture, more than genetic or other biological inventions did. Here is a 1935 Soviet movie Gibel sensatsii (“Death of a Sensation”) about a workers’ revolution against a capitalist served by his giant metal workers. He controls them a wonderful way, through broadcast of theremin-like gestures. In a wonderful scene the isolated capitalist plays the saxophone and his giant “robots” dance. I love that scene! Note the label on their metal chests: R.U.R.

THE COMEDY OF EMPIRE

While Karel Čapek's novel The War with the Newts (1936) explores exploitation and societal power structures, it’s also an exploration of human folly. Evolution has its own agenda, and is not subject to human control. In storytelling method, it reminded me very much of Dos Passo’s USA trilogy (first volume, The 42nd Parallel , published 1930), which has a kaleidoscope presentation of a large landscape of characters, regions, and time. I don’t know if Čapek read Dos Passos, or if this method commonly reflects the jazz, radio broadcast, newsreal spirit of the times. Dos Passo’s treatment includes newsreel text, style, and broad knowledge of characters in different regions demonstrating momentous change linked to time and place. Newts is like that, with excellent portrayals of character, their manner of talking, point of view, and situations in different parts of the globe. It does not include Dos Passos style newsreels, but uses different fonts and other typeset tricks to help sample individual, varied moments of communication across the planet. It adds up to quite a literary achievement, and aside from the actual plot, shows the breadth and depth of knowledge of an alert, connected writer. In Newts, you can see how his dramatist’s ability to mimic the speech of different classes, professions, generations, and cultures enriches his prose fiction.

The newts are a salamander-like species of sentient but primitive humanoids. Captain Lindsay observes, “They're a new race altogether... damned intelligent and progressive... they've got a jolly good social system, all right…” (Chapter III). Bred for our use, individuals, then companies, want more and more of them, then the world’s navies take them on. In industrial vats, they rapidly increase in number and speciality. As they do, the humans think they are exploiting them for profit or other gain, guiding their evolution. By the end of the book, the human world receives a surprise.

Whoopsie! The exploitation, under the supreme reign of Nature’s laws, goes both ways. Yes, the humans in the novel exhibit greed and a sense of racial superiority, mirroring real-world colonialism: “We brought them civilization, after all…” (Chapter XI). What happens when you civilize an intelligent species with language, education, machines, radio, other technology, to make them more efficient captive labor? The ending of the novel goes in an unanticipated direction, one that changes whole continents, but maybe it should have been anticipated.

In an interview, Čapek explained how he came to write “Newts”:

"I had written the sentence, 'You mustn't think that the evolution that gave rise to us was the only evolutionary possibility on this planet. . . . If the biological conditions were favorable, some civilization not inferior to our own could arise in the depths of the sea. . . . What would we say if some animal other than man declared that its education and its numbers gave it the sole right to occupy the entire world and hold sway over all creation?"

THE COMEDY OF LEFT AND RIGHT

Karel Čapek's was wary of both the Left and the Right. His writings reveal a concern about dogmatism and abuse of power. For that same focus, I assume mainstream understanding of left and right labels. The uniting factor here is Čapek's opposition to dogmatism and abuse of power.

Čapek did not fall for leftist utopian ideals that ignored human complexities. In his play, “The Gardener,” he uses the metaphor of a scientist attempting to engineer a perfect society through selective breeding, a theme similar to R.U.R. and The War of the Newts. The play ends in dystopia, highlighting the dangers of unchecked utopian visions. As one character warns, “Don't try to improve mankind...it doesn't work.”

In his essay “Why I am Not a Communist,” Karel Čapek outlines his reservations towards communism. He finds the ideology's focus on absolute equality unrealistic, arguing, "People are not equal... they are unequal in every way." He further criticizes the potential for a communist system to stifle creativity and individuality, stating, “Art cannot be created by a committee.” Čapek ultimately advocates for a more nuanced approach, seeking a society that balances social justice with individual freedom. He also explains that he is not a communist because of his sympathy for the poor. In a last human barricade, surrounded by murderous robots, the engineer Alquist laments his project but remembers his motivation: “I am REVOLTED by poverty!”

However, Čapek wasn't blind to the shortcomings of the Right either. His play, The White Plague (1937) anticipates the invasion of a small country by an adjoining larger one while a hideous, disfiguring disease spreads across the land. Nazi Germany annexed and occupied Czechoslovakia in stages from 1938-1944. The War with the Newts shows abusive colonial relations even before the Newts appear. In both R.U.R. and Newts, a similar plot arc brings the exploiters to punishment; through their arrogance, they have become the inferior “other”. Čapek advocated for a more nuanced approach to politics, one that valued individual freedom and critical thinking over blind adherence to ideology.

Is it fair and helpful to call Karel Čapek a radical centrist of his time? He distrusted utopian ideals and rigid ideologies, advocating for a more balanced approach. Devoted to democracy, his works often champion individual freedom and critical thinking over blind adherence to a particular political ideology. The context “of his time” is important to remember, its extremes, so geographically close. Čapek's core values seem more aligned with humanism than a strictly centrist perspective. He emphasized empathy, reason, democracy, and justice.

I don’t yet have great insight into Czech culture or literature, but fortunately, like Ben Franklin in Paris, wearing a fringed leather jacket and coonskin cap, Substack’s Central European correspondent

has that covered. If you’re interested in literature, please take a look. Whereas, I might talk and act like Foghorn Leghorn, he offers multilingual erudition on literature, which nicely offsets the dulcet white wine tones of California. From his writing, I learned that Czech culture offers something unique, a heritage that mixes Slav and German. What a combo! It’s something for me to think about as I play my saxophone and make my metal giants dance.Many of Čapek's works have been made into movies, not all with English subtitles. This is an outrage! (A joke—or maybe it was robot cramp, followed by smashie-smash?) There are some productions of R.U.R. on YouTube in English. There is a new film, a biopic, “Hovory s TGM” (“Conversations with TGM”) that dramatizes the conversations between Čapek's and Czech foundational statesman TG Masaryk. In something of a literary accident, his statue in Washington D.C. figures in my novel A Whirly Man Loses His Turn.

Here is an English translation of the movie description:

Jan Budař as Karel Čapek and Martin Huba as T. G. Masaryk excel in the story of one of the most famous conversations in our history. The film "Conversations with TGM" brings unexpected tension, emotions and a clash between two important men to the cinema screens.

Masaryk shows that he is not only a founding father and a cool textbook icon, but a man of flesh and blood. In addition to his plot-creating ideas, he reveals his ability to intrigue and also talks about his love affair and rediscovered sexuality. [Uh-oh! Uh OH.]

The clash of two giants from different generations has explosive potential, even though their only weapons are walking sticks and words.

Portland, Oregon, 2020: It was a hard year for the narrator to keep making jokes and being a pest. A woman with a laptop has sorrow, because her hour of PowerPoint has come. First there was a baboon for president that made everyone batty, then there was a pandemic shutdown that increased the crazy. As a Diversity Officer plots against a trash-talking conservative doctor, her daughter radicalizes. Her mom's second marriage to a younger man develops friction, which another man wishes to exploit by taking him to bed. A slight lift in the state's rules for pandemic lockdown allows a birthday party… that unleashes the conflicts. And as this anarchy happens, the forests begin to burn, and so do the streets. Was justice coming? What does it all mean? In this novel there's trouble over the discourse between the narrator and an elusive and powerful Masked One. As plywood awaits the broken windows, punishment awaits the wrongdoers... those who strayed against the discourse, not the anarchists. What to make of it? I say nothing. 500+ ILLUSTRATIONS

Reviews

Our narrator, fond of naughty jokes, struggles to keep making them in a newly censorious environment. Around him, the world seems to be going mad and calling it social justice. Is it? Oh, I thoroughly enjoyed Fragility. The city of Portland, one of America's most progressive, rises from the pages almost as a character with its own arc. It asks a lot of awkward questions... And there's a passionate appeal for humour. Without it, how can we hold the powerful to account? Woods draws on jokes made by Soviet dissidents to illustrate this in a very clever way. And a big shout out to the impactful and sometimes disturbing illustrations that punctuate almost every page. I found them quite mesmerising. ...I enjoyed all the references in Fragility and I think readers will, too. Recommended. That is, if you agree with Woods that it is hard to purge all of our heterodox opinions. I agree. It is. --The Bookbag UK

A brilliant literary tale of upheaval and discord... Woods presents a satirical exploration of the societal shifts and political tensions emerging in Portland, as the city cautiously emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic... The novel challenges readers to ponder uncomfortable questions about the efficacy of social justice movements, the consequences of ideological extremism, and the role of humor in holding the powerful to account. ...A must-read for those willing to confront uncomfortable truths and engage in critical reflection on the complexities of modern society. --The Prairies Book Review