Oh Native Land! Bu-Bu-Bu, Miaow, Miaow

Methods of Soviet literary dissent offers tools for those who write stories without permission

Copyright © 2023 Mosby Woods

PROSECUTOR:

Please don’t lecture us on literature.[1]

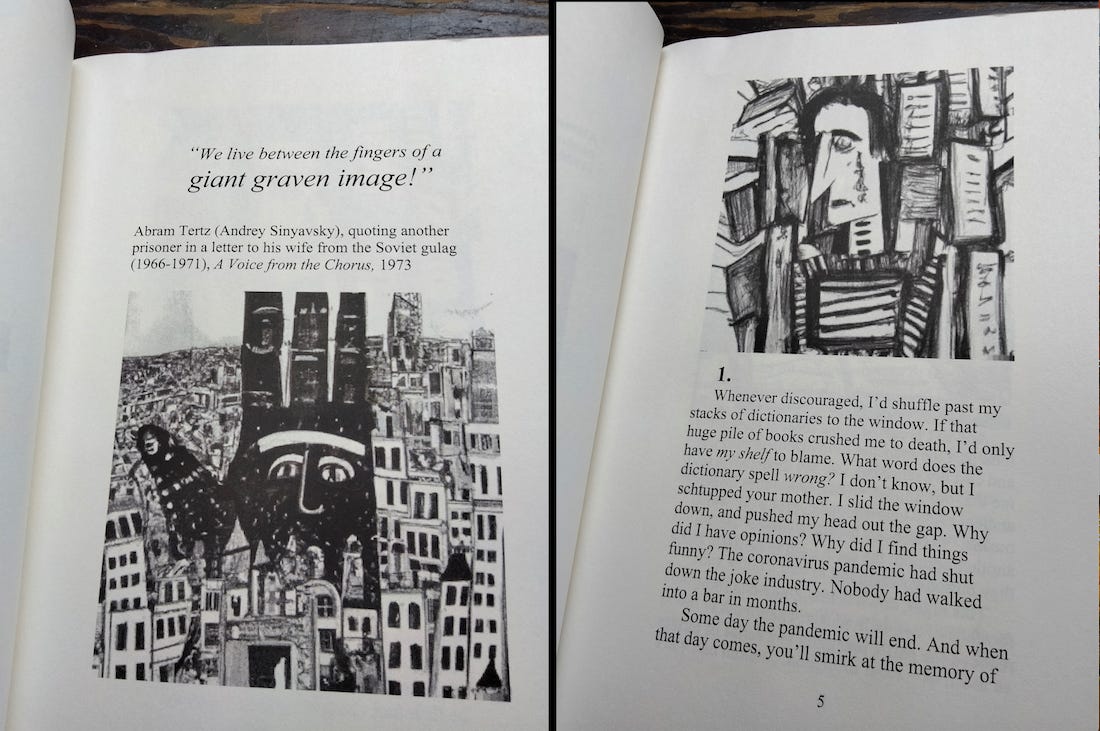

Note to Substack readers: During the 120 days of riots in Portland, I wrote a novel about what was happening. This was possible because I based its structure on the plot of a Soviet novel of dissent. Just as I can read Abram Tertz’s The Trial Begins and have a sense of “the Doctor’s Plot” in Moscow 1951-53, my hope is that a reader 50 or 150 years from now could read my novel Fragility and understand Portland’s willful decline in 2020. In 2021, I wrote this essay below to explain my thoughts on the relevance of examples of Soviet literary dissent for American writers at this time.

Set in Moscow just days before Stalin’s death, the novella The Trial Begins (1960) describes the private lives of a prosecutor’s family as it blunders toward destruction. The narrator is a character too, visited by a phantasm he calls “the Master,” who bids the narrator to exalt the prosecutor.

This means the mission is consistent with Soviet purpose-driven art, Socialist Realism.

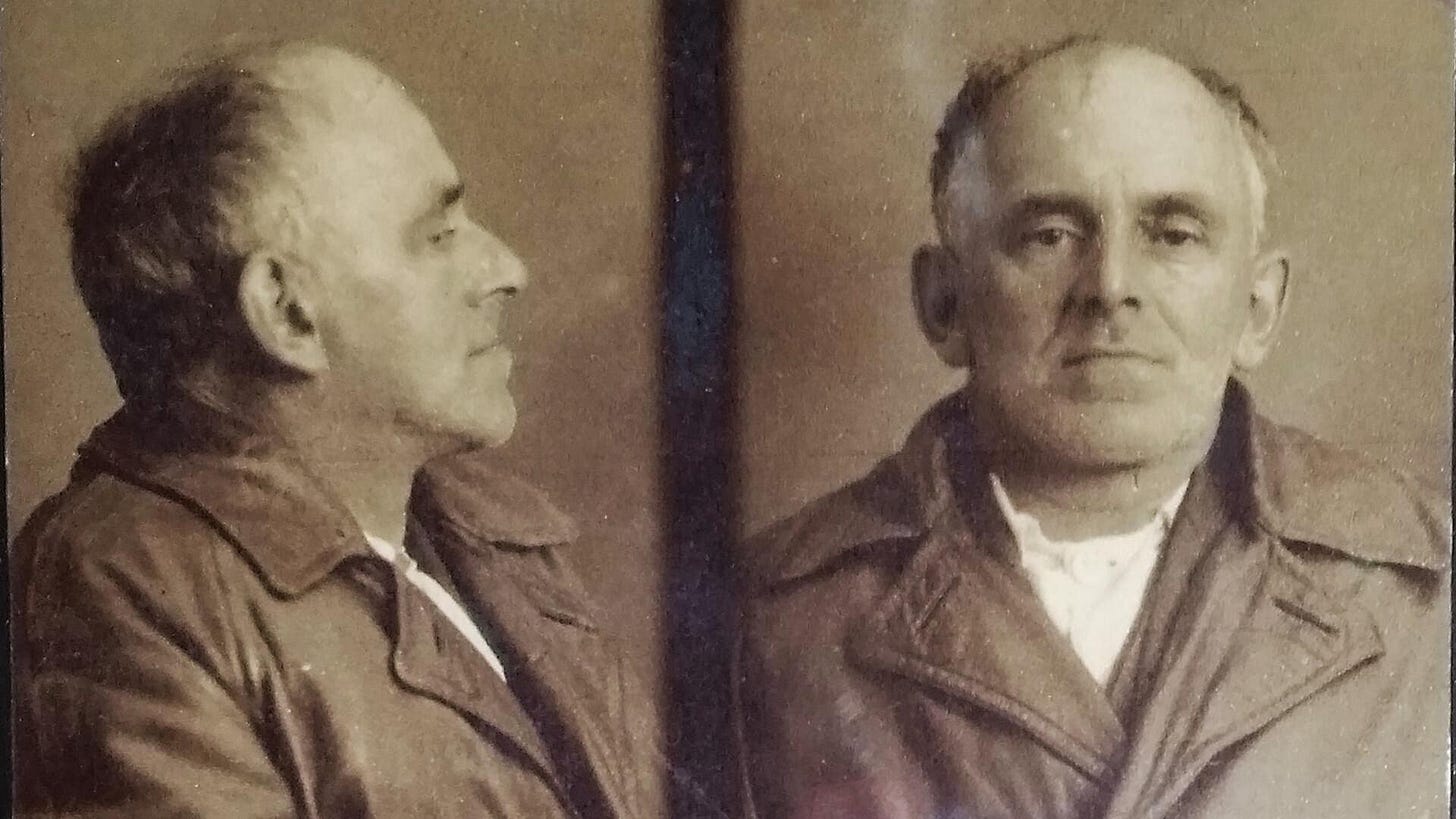

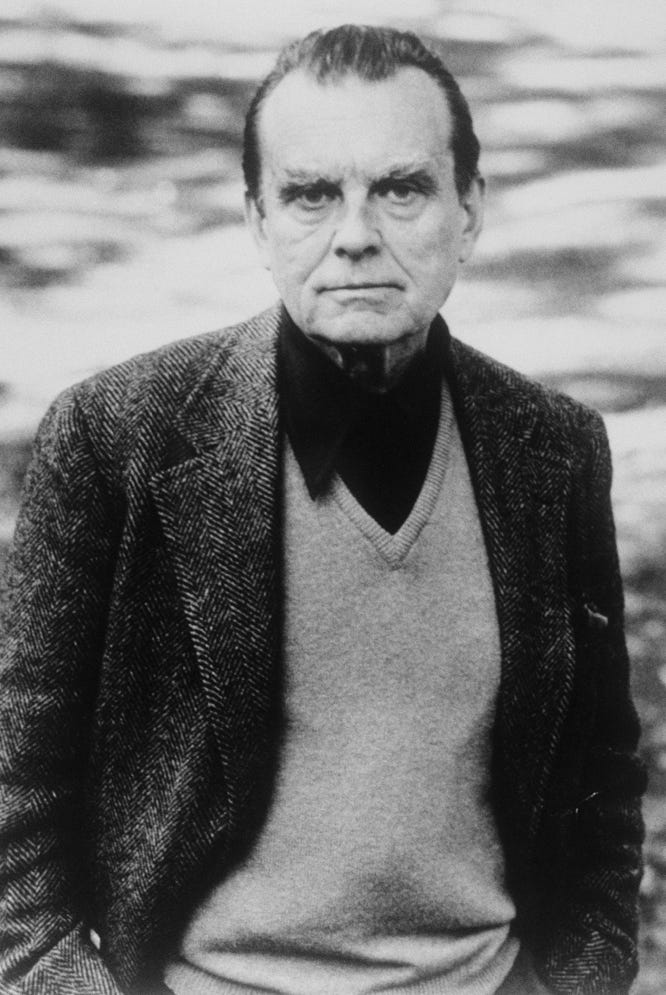

The extraordinary 1966 Soviet trial of writers Andrei Sinyavsky (“Abram Tertz”) and Yuri Daniel helped mark the end of the Khrushchev Thaw. It includes literary exchanges… Are the views of the first person narrator Sinyavsky’s views?

SINYAVSKY: The “I” in the story is neither Sinyavsky nor Tertz; he is the fictitious author, whose mood is one of fear and exhalation. Kolyma [a gulag] would be the logical end of the road for him. This is not reality, but something that appears to the author in his nightmares…

JUDGE: But the abortion is real! Why was that brought in?

SINYAVSKY: It is mentioned, but not shown. In literature there is the notion of conventions.

JUDGE: We’ll talk of literary conventions later. You have depicted the Russian people as drunkards.

SINYAVSKY: I can give a detailed answer to that. (Laughter in the courtroom.)[2]

Tertz’s novella opens on the waning weeks, in 1953, of Stalin’s anti-Semitic Doctors Plot, which itself came right after the execution of thirteen Soviet Jews. The name “Abram Tertz” might have come from a bawdy drinking song about a Jewish gangster.[3] Andrei Sinyavsky (1925-1997) was not Jewish; this was provocation.

Sinyavsky’s use of that pseudonym is Aesophic. A genre, Aesophian language uses tactful wording, or semi-hidden identification, myth or animal fables to disguise dissident expression and trick censorship. It’s naturally satiric. There’s a mischievous insincerity to a senior research fellow at the Gorki Institute of World Literature who claims the crude criminal persona of a tavern song. It’s obviously unbelievable, a joke about himself, a declaration of spirit. His pseudonym failed to protect him from arrest, but did protect him from the coercion to lie. His insincerity prevented him from any overly sincere false aesthetic, from kitsch. It promised a lot of mock-irresponsible trickery in pursuit of truth. This tonic recharged my fizz as I reread him in Portland during the cultural revolutionary unrest of 2020.

In The Trial Begins, the prosecutor Globov prepares a case against Rabinovich, a Jewish abortionist. Globov dotes on Marina, his young wife. He tries to steer his idealist son Seryozha from Trotskyite error. Karlinsky, a defense lawyer and Soviet psychopomp, takes Globov’s wife on dates. At night the seducer fears death. At Marina’s birthday party, Karlinsky’s attentions cause the jealous husband and wife to fight. It turns out his wife aborted their child to preserve her figure.

Globov hobnobs with colleagues such as Skromnykh, domestic needle-pointer and State Interrogator. Why the needlepoint? Tertz refuses to caricature for political points. Only the “liberal” public defender is loathsome.

In Tertz’ fiction, something stalks the realism… an excess. What is it? To start with, things that should be inanimate sometimes playfully come alive in ways the reader can’t take literally. These caprices carry ironic enjoyment but also different levels of oddity. This includes word play, rebellion, a jester attitude of resistance to kitsch and its politicized claim on reality. Early paragraphs of The Trial Begins shows secret police attention to the narrator’s manuscript:

He ran his hand over the first page and, presumably by way of censorship, scooped up all the characters and punctuation marks. One flick of his hand and there on the blank paper were a writhing heap of purple marks.

One letter — I think it was an s —flicked its tail and tried to wiggle out, but he deftly caught it, tore of its legs, and squashed it under his fingernail.[4]

The excess of realism may also appear underfoot as a strangeness of plot, such as in his short story “Pkhentz.” An alien creature, marooned in a Soviet tenement, withers in unhappy disguise. He has taken the name Andrei, same as the hidden author. Reveal himself? “No, I’d better put up with living lonely and incognito.”[5]

The speaker is an Other. In Sinyavsky’s testimony above, authority forced him to clarify, “The ‘I’ in the story is neither Sinyavsky nor Tertz.” From Soviets to social media, an acute need to self-monitor confuses narratives. The natural need for narrators to create personas drifts into falsehoods, roles, and disguises.

Tertz’s story “You and I” offers a surplus of paranoid intrusions that undermine a festive gathering with no basis for suspicion… except for a surveillant second person narration. Does the narration itself confirm the suspicion, or reflect a continuum of social malady and mental illness? The hidden narrator, a kind of double, speaks of the main character as You. It interprets the world around the You as trap, subterfuge, fractious, calculated… anything but a natural, easy wholeness.

But you gave not the slightest sign of attaching any importance to the ominous phrase “Let’s begin,” as though these words blurted out by Graube’s henchmen had nothing suspicious about them and conveyed only an innocent invitation to eat and drink.[6]

***

The guests ate rapidly, clicking their knives and forks and thereby communicating with each other in a secret code, like Morse.[7]

The You character cannot resist the delusions perceived in his point of view by the observer. The narrator is thus a perpetrator of the object’s hyperboles of suspicion. Suspicion ruins the celebration; subject and object, nearly identical, compete for the same woman. Self-consciousness shows as a mystic gesture of menace, an “all-seeing eye that had been watching them… dissolved in a yellow patch, the color of wallpaper, as if it had never been there.”[8]

The spying double of “You and I” demonstrates another Tertz technique of excess, phantasmal juxtaposition. Tertz’s The Trial Begins continues with prosecutor Globov’s inner life in eerie pursuit of the outer world in a way no dialectical jargon could contain. “Falling asleep was like sitting down before a television set which had not been properly tuned in.”[9] Thus in dream he follows the real (fictional) visit to the museum by his wife and the defense attorney. This impossible situation grows stranger when Dr. Rabinovich appears.

The excess is impossible. It dissembles, feigns ignorance. It is not quite insincere but insincere… I italicize it to convey the idea that its unruly attitude toward realistic fiction crosses lines, but does not break verisimilitude. It has something to say about the real world.

Excess shows as wild private musings of characters, such as Karlinsky’s Swiftian proposal that engineers unwanted fetuses to the communist project. (Sinyavsky had to argue in court that they were the repulsive character’s views, not his own.)[10]

Other times Tertz’s surplus erupts in the prose itself as playful rhetorical tricks… In his autobiographic novel Goodnight!, prisoners greet the news of Stalin’s death with a lumpen proletariat synecdoche: ‘The mustache croaked! The mustache croaked!’”[11] Tertz’ treatise On Socialist Realism (1959) refers to the silence of “the mystic mustache.”[12] The part means more than the whole, more than the mortal man Jughashvili; it ridicules the Stalin persona, his cult, his phantom, their collective superego.

When the Tertz trial was due to begin, “Konsomoloskya Pravda” published an 1828 letter from the Tsar that directed an end to the prosecution of Pushkin for a blasphemous poem.[13] Like this letter, and his pseudonym, Tertz’ excess sometimes follows the tradition in literature that (again) remembers Aesoph’s fables as a way to mask dissent behind placeholders, indirect comment and parallels. Tertz’s 1963 novel The Makepeace Experiment tells the story of a bicycle repairman who uses magical mind control to try to make his village a utopia. He makes it worse.

The roots of Tertz’s style follows the current of Russian literature conscious of folklore and E. T. A. Hoffman (1726-1822), whose stories sift German folkloric intrusions into regular life. These impositions — fantasy, dream figures, outlandish personalities, and shadow — prefigure surrealism through the plight of contemporary characters, such as inhabit his extraordinary story, “The Sandman” (1816). Tertz named his collection of Fantastic Stories after Hoffman’s collection. He modeled the plot of his novella Little Jinx (1992) on Hoffman’s novel Little Zaches, Great Zinnober (1819).

The saber points of Hoffmann’s sideburns point through Gogol, Dostoevsky’s The Double, Zamyatin and the writers’ group “Serapion Brothers”, Olesha, Bulgakov, and others. Irrational, unconscious, mischievous, and capricious intuitions leap into daily life to make tonal connections and echoes. The roundedness, the narrative twinkle, ironic reverie and fantastic transports makes the routine events curious, and grim events more bearable.

Sinyavsky co-wrote a book on Picasso, and specialized in the creative and Russian Silver Age literature (early 20th century to ~1930). The Russian Silver Age includes Symbolists such as Andrei Bely, whose Petersburg (1913) uses a type of prose synesthesia, a color of sound, to estrange the distressed landscape, and father-son conflict, under 1905 revolutionary stress.

Bely uses prose estrangement for mystic connection. When Tertz manipulates language, it’s private disobedience to ideology, a scratch or graffito upon the suffocating membrane. In “Pkhentz”, the fugitive entity cries up to his home star with a mix of languages and post-Joycian burbles. This is an all-caps ending of earthly echolalia and the title word, an untranslated alien marker of identity:

“Oh native land! PKHENTZ! GOGRY TUZHEROSKIP! I am coming back to you. GOGRY! GOGRY! GOGRY! TUZHEROSKIP! TUZHEROSKIP! BONJOUR! GUTENABEND! TUZHEROSKIP! BU-BU-BU! MIAOW, MIAOW! PKHENTS!”[14]

Estrangement by language is morbid liberation. In “You and I”, a character momentarily freed from You-identification repeats the Russian equivalent of “eenie-meanie-minie-moe” over and over. “He thought that if he disengaged his brain, he would rid himself of the snoopers who were spying on him from within.”[15]

Tertz’s playful misreplication of cant demonstrates the resilient spirit behind his insincere, surplus realism. In The Trial Begins, Tertz makes a collage of jargon fragments. Party loudspeaker estrangements resound with the mental ruin of ideological catch-phrases and state paranoia:

“Objectively speaking... The logic of the struggle... The wheel of History... Agents of Imperialism... Backwards... He who is not with us... Encirclement… *** Counter, xism, ism, ism, ism… Principle… inciple… Jective… Manity… lution…”[16]

Consider how surplus as self-censorship mocks the meaning of the sentence, as if there’s too much secrecy, too many spy centers for reality to bear…

In strict confidence he told her that spy centers were found in X-garia and Y-akia.[17]

This ridiculous attempt at code is funny because it’s insincere, transparent. It means for the reader to decode it: In strict confidence she told him that X-cism and Y-iarchy were found in certain E-mails.

Tertz can unbinds metaphors and analogies from mere sentence roles to participate in the reality-sense of the story. In a zoo, “Monkeys hastily rehearsed the neurotic gestures of intellectuals. Crowded in their common cell, parakeets chirped away like typewriters.”[18] Elsewhere, the notes of a Soviet orchestra’s performance expresses a metaphor of a flood that drowns the bourgeoisie, which goes on to flow over the audience and overtake the Soviet elite in attendance. “A general’s wife in evening dress floundered, tried to scramble of a pillar, and was washed away.”[19]

Tertz winks. He expects the reader as co-conspirator to understand that this is not the literal truth. It’s insincere, a comment on the ideological music and Soviet classes. The style is not merely satirical, but teasing. It offers to share a dissenting smile with the reader.

The mustache of permission flutters, persistent and companionable. There is something personal, forbearant, and humorous about Tertz’s attitude toward it. From the gulag, Sinyavsky wrote his wife, “Two writers, Hoffman and Dickens, …have revealed to us that God takes a humorous view of mankind. In humor there is both tolerance and encouragement: ‘Bravo!’”[20]

In 2018, John Wilson, writing of Sinyavsky in First Things, quotes Tertz’s own use of the words of Osip Mandelstam:

I divide all works of literature throughout the world into those permitted and those written without permission.

Then Mr. Wilson muses…

What would it mean for a writer in the United States today — a Christian like Mandelstam and Sinyavsky, but working in a society and a time very different from theirs — to write “without permission”?[21]

What does “permission” mean for contemporary writers in the USA? The clanking lines of Amanda Gorman’s inaugural poem articulate the progressive spiral, our superego in haute couture:

being American is more than a pride we inherit —

it’s the past we step into

and how we repair it.[22]

Being American is, for Gorman here, simple, wholly political, and comes with obligation to a creed of progress. (Compare, from Audre Lorde, “and sit here wondering / which me will survive / all these liberations.”[23]) How can we “step into” the past? It’s gone. If part of “being American” is “how we repair it,” and “it” is a past grievance, who decides which grievance, and who today pays for it? (Compare, from Carl Sandburg, “I am the grass. /Let me work.”) [24] “Achievements,” Tertz observed in his famous essay, “are never identical with the original aim.”[25]

Our Mustache of Permission swoops, its mothy arabesques more aloof than the Soviet. There are no gulags for disagreement, just self-exile, silence and shame… occasionally worse. If you engage your internal censor, you need not bother the institutional gatekeeper to reject you. Self publication is available to all, much like sleeping under a bridge. Literary dissent becomes just another voice of vanity that cries, “Look at me!”

Both my copies of The Trial Begins include Tertz’s On Socialist Realism. It’s part of the same Cold War sensation he made as a dissident. In his introduction, Czesław Miłosz called its style “a kind of lyrical rage.”[25]

In seventy-two pages, Tertz argues that socialist means religious. It’s a faith in a Purpose toward a fulfilled Communism they will never see and can’t imagine. In other words, it’s unreal. Realism did not suit this:

“We are helpless before the enchanting beauty of Communism. We have not lived long enough to invent a new Purpose and go beyond ourselves — into the distance that is beyond Communism.”[26]

Tertz explains problems of plots based on capital-P Purpose, on happy endings, on the Positive Hero. He describes how sanctioned Soviet writers attempted to paste the cracks of their realism’s failings with elements of other genres. (This critique may have insight toward Tertz’s literary method of dissent.) To support the unknowable Communist aspirations, Socialist art needed to set aside ideologically sincere realism.

Tertz concludes,

“. . . I put my hope in a phantasmagoric art, with hypotheses instead of a Purpose, …May the fantastic imagery of Hoffmann and Dostoevsky, of Goya, Chagall, and Mayakovsky. . . teach us how to be truthful with the aid of the absurd and the fantastic.”[27]

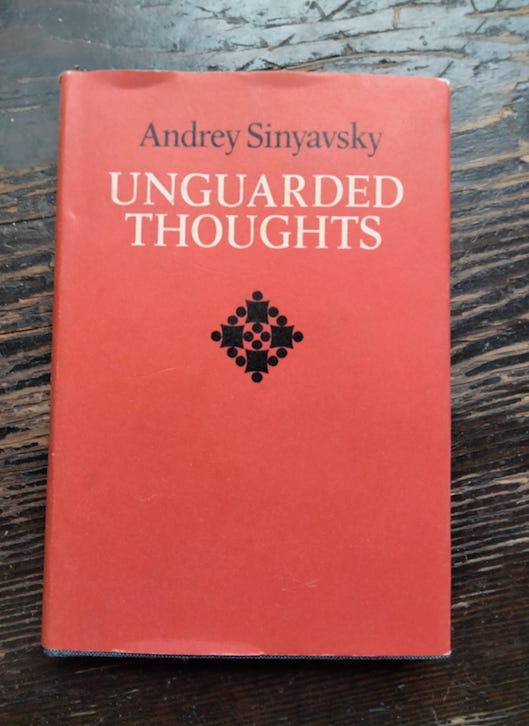

Truthful by means of the absurd and the fantastic! How did he come up with that shocking insight? Maybe Tertz’s narrative excess resonated from his spiritual beliefs. His little book Unguarded Thoughts includes a mix of profane and devout ruminations:

"What is a body? An outer covering, a diving suit. For all you know, as I sit in my diving suit, I'm squirming all over..."[28]

The absurd and fantastic relation between his body and his soul might be something like his sense of an outer covering of language, and, within it, a narration of squirm.

Writhing, Americans do still have free speech. But something, not a mustache, hovers on cherub wings. Capital-P Purpose now glosses official American culture with kitsch sincerity. Gorman articulated this gloss:

We are striving to forge our union with purpose.

***

We lay down our arms

so we can reach out our arms

to one another[29]

That sincere cloy and purpose, a moral fashion show, an identity filter,[30] plus your submission of a diversity statement… these might constitute some of the requirements for our phantom Mustache’s permission. Gugenheim and MacArthur fellow Ibram X. Kendi explained this purpose, how we must reach out our arms to one another: “The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination.”[31] This ouroboros progress assures there will always be a past discrimination, always a present discrimination, and always an authority to deny permission on the basis of ideology.

However, plenty of examples of unsanctioned fiction, including Tertz’s The Trial Begins and Joyce’s Ulysses, show that no one needs permission. With notoriety, defiance of permission helped sales. Literature is banditti: we don’t need no stinking badges. Quality, publication, and notice remain as questions. As for paying the bills… what is new?

How would Mr. Wilson ever know about a writer that answers his query? Maybe he should have specified, what Western publisher will risk resources and young staff unrest? The Soviet Union published Sinyavsky, but never Tertz. His persona’s lack of Soviet permission made his outlaw titles a hot commodity in the West, and infamous in the USSR. Now the USSR is gone, and Tertz’s books in English are out of print.

Amanda Gorman’s sincere books indeed do sell, with numerous five-star reviews. Some of the clerisy of the canon know better, but are afraid to tell the truth. This is what, in The Captive Mind, Czesław Miłosz calls “Professional Ketman”, a method of intellectual cope under tyranny.[32] Maybe the contemporary dynamic isn’t all that new, an ageless Mad Libs with fashionable fill-ins. There are always exceptions: The Soviet Union did publish some works by Solzhenitsyn.

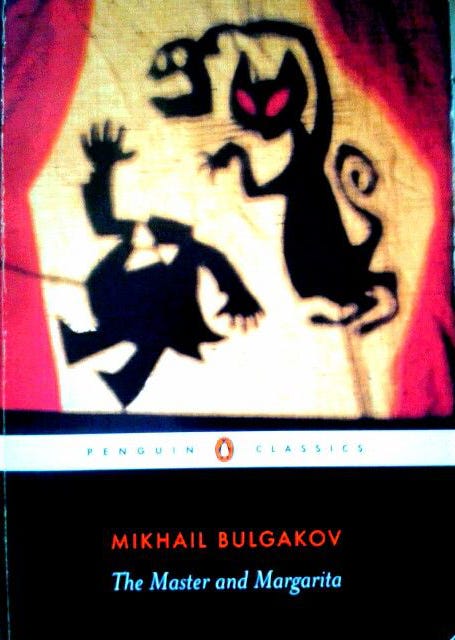

I once had a teacher who read us a poem he wrote, then tore up the page and discarded it. He asked, “Does the poem still exist?” In Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, after the character known as the Master burns his manuscript about Pontius Pilate, Professor Woland’s talking cat Behemoth retrieves it unharmed. Woland, Bulgakov’s devil, famously exclaims, “Don’t you know that manuscripts don’t burn?”

Unfortunately, without readers, writing is an art with only this metaphysical solace. Permissionless writers today can enjoy cold, silent, gnostic victory. What is new? But Mr. Wilson and few others[33] [34] [35] will wonder, where are today’s dissenting American writers?

Near the end of The Trial Begins, fearing the new “roundup,” Globov disowns his arrested son. Marina yields to Karlinsky’s bed, but he fails to perform.

The Master (Stalin) dies; on the streets of Moscow, a mob of mourners trample Marina. The narrator tears up his manuscript. State agents piece it together. The prosecutor Globov has lost baby, wife, and son. What he has left is ideology, Purpose, to which he recommits himself.

Finally, in the Kolyma gulag, the narrator, Seryozha and Rabinovich dig. The doctor unearths an old cross-shaped dagger, and exclaims a procession of teleological progress: Where next?

“In the name of God! With the help of God! In place of God! Against God!” He really did sound like a madman now. “And now there is no God, only dialectics. Forge a new dagger for a new Purpose at once!”[36]

A Rabinovich in our American moment could exclaim:

“And now there is no God, only equity.”

How can all outcomes of diverse humanity become equal? Portland shows the way: with gunshots in the night, with impunity to smash, with arson and carjacking, with sidewalk camps and middens, with virtue signals and vertigo, with a continuum of social malady and mental illness and administration. As Pasternak wrote, “The yelling furrows the wind.” (“February,” 1912.)[37]

Tertz found a way to smuggle his manuscripts of dissent into that forbidden land, the marooned future… our alien now. During the pandemic days of 2020 unrest in Portland, nouns marched with verbs: slogan, preach, and coercion. At night, the adjectives stepped forward, lead by an adverb the district attorney refused to prosecute: cruelly, extreme, and ruinous. How to remember this when most gatekeepers demand an approved ideological understanding? It might again take insincere integrity in order to be faithful. BU-BU-BU! MIAOW, MIAOW! BONJOUR! GUTENABEND! TUZHEROSKIP! AMERICA!

Portland, Oregon, 2021

Note to Substack readers: The problems in Portland continues. No institution supports me. You can pick up the paper or ebook versions of this essay and my novel Fragility. Both are illustrated.

Bibliography

Court Transcript. On Trial: The Soviet State versus “Abram Tertz" and "Nikolai Arzhak", (Max Hayward, trans.) New York and Evanston: Harper & Row, 1967.

Gorman, Amanda. “The Hill We Climb”. https://thehill.com/homenews/news/535052-read-transcript-of-amanda-gormans-inaugural-poem.

Lorde, Audre. The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde, New York: W. W. Norton and Company Inc., 1997.

Miłosz, Czesław. The Captive Mind, (Jane Zielonko, trans.). New York: Vintage Books, 1955.

Pasternak, Boris. February: Selected Poetry of Boris Pasternak, (Andrey Kneller, trans.). Boston: Kneller, 2011.

Tertz, Abram. The Trial Begins and On Socialist Realism (Max Haywood trans.). Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982.

Tertz, Abram. Fantastic Stories, (Manya Harari, trans.). Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 1987.

Tertz, Abram. Goodnight!, (Richard Lourie, trans.). New York: Viking Penguin, 1989.

Tertz, Abram. The Makepeace Experiment (Manya Harari,trans.). Evanston: Northwest University Press, 1989.

Tertz, Abram. Unguarded Thoughts, (Manya Harari, trans.). New York: Collins & Harvill, 1972.

Tertz, Abram. A Voice from the Chorus, (Kyril Fitlyon and Max Hayward trans.). London: Collins & Harvill Press, 1976.

Also by Mosby Woods:

Fragility

A Whirly Man Loses His Turn

Jack O’Lantern Skull Robotnik

Footnotes

[1] On Trial, p. 94

[2] Ibid., p 96.

[3] Definitive claims lack primary sources, to my knowledge.

[4] The Trial Begins and On Socialist Realism, pp. 5-6

[5] Fantastic Stories, p. 236.

[6] Ibid, p. 4.

[7] Ibid, p. 5-6.

[8] Ibid, p. 8.

[9] The Trial Begins and On Socialist Realism, p. 66

[10] On Trial, p. 94

[11] Goodnight!, p. 15

[12] The Trial Begins and On Socialist Realism, p. 216.

[13] On Trial, p. 31

[14] Fantastic Stories, p. 245.

[15] Ibid., p. 27.

[16] The Trial Begins and On Socialist Realism, p. 85.

[17] Ibid., p. 80.

[18] Ibid., p. 64.

[19] Ibid., p. 22.

[20] A Voice from the Chorus, p. 60.

[21] First Things, “Thinking Under the Influence”: https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2018/06/thinking-under-the-influence

[22] Amanda Gorman, “The Hill We Climb”.

[23] Audre Lorde, “Who Said It Was Simple”, The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde, p. 92.

[24] The Trial Begins and On Socialist Realism, p. 163.

[25] vCarl Sandburg, “The Grass”, The Complete Poems of Carl Sandburg, p. 136.

[26] Ibid., p. 136

[27] Ibid., p. 154.

[28] Ibid., pp. 218-219

[29] Unguarded Thoughts, p. 57.

[30] Gorman, ibid.

[31] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/may/16/how-women-conquered-the-world-of-fiction

[32] Ibram X. Kendi, How To Be An Antiracist. “The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.” https://highlights.sawyerh.com/highlights/Wc3cIP436n60JRoYYTVe

[33] The Captive Mind, pp. 69-71, describes Professional Ketman. “Finding oneself in the very midst of an historical cyclone, one must behave as prudently as possible, yielding externally to forces capable of destroying all adversaries.”

[34] https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/saul-bellow-saw-it-coming/

[36] https://thecritic.co.uk/where-is-the-waugh-or-wodehouse-of-our-time/

[37] “If you were a novelist right now, think of what you could do!” Rod Dreher, April 22, 2021, General Eclectic 16 Podcast, Locked Down in Budapest and Reading the Signs of the Times, 40:42

[38] The Trial Begins and On Socialist Realism, p. 126

[39] February: Selected Poetry of Boris Pasternak, p. 2.